The Book of Common Prayer, also referred to as the BCP or Prayer Book, is a standard work of liturgies, prayers, rubrics, calendars, and historical documents that provides a foundation for shared worship by every Protestant Episcopal Church (PEC) diocese and congregation. Despite its importance, or perhaps because of it, the BCP is not static. It may be updated and supplemented as necessary by the agreement of two successive General Conventions; occasionally, it is completely revised to meet the needs of the emerging church. These changes are governed by Article X: Of the Book of Common Prayer and Canon 3: Of the Standard Book of Common Prayer in the Constitution and Canons.

Like The Episcopal Church itself, the church’s BCP was born out of the American Revolution (1776-1783). No longer could American clergy pray from the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, which required that they pray for the head of the Church of England, the King1. They would need a prayer book of their own. Although the discussion started earlier in state conventions, the problem of the Prayer Book was raised at the first General Convention in 1785, which was concerned with “the importance of maintaining uniformity in doctrine, discipline, and worship” in the church. The Convention resolved to base its revision work on the familiar Church of England BCP, but to make changes “as shall render it consistent with the American revolution and the Constitutions of the respective States,” and it appointed a C committee for this purpose.

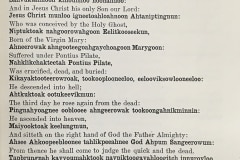

The initial attempt at a new Prayer Book, The Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments, And other Rites and Ceremonies, as revised and proposed to the use of the Protestant Episcopal Church, was certified early in 1786 and drew considerable debate at the General Convention held later that year. Editing continued until adoption in 1789. The new Book of Common Prayer was certified for use on October 1, 1790. This would remain The Episcopal Church’s BCP for over a century, the next major revision not being adopted until the 1892 General Convention, although revision work began in 1880. A third revision would be adopted by General Convention in 1928.

The fourth and most recent revision of the BCP was adopted in 1979. It reflected the participation not just of theologians and clergy, but of the whole church through the trial use process. As the Standing Liturgical Commission wrote in their 1976 Blue Book report, “no other method could have resulted in the production of so comprehensive and so rich a book of common worship, bringing together within the covers of a single volume so wide a spectrum of traditional and contemporary forms.”

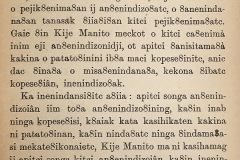

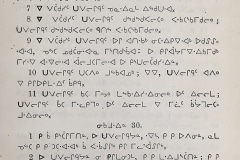

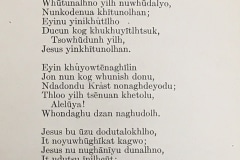

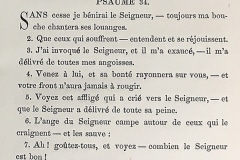

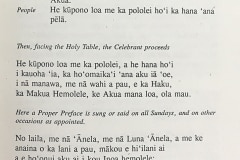

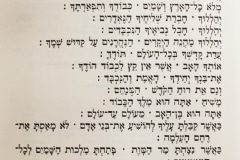

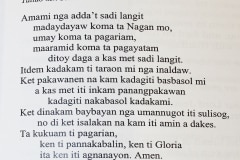

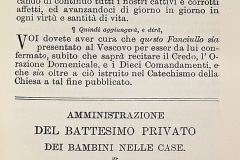

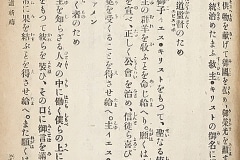

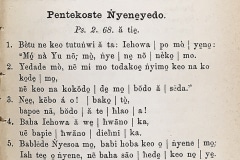

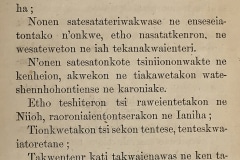

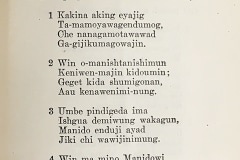

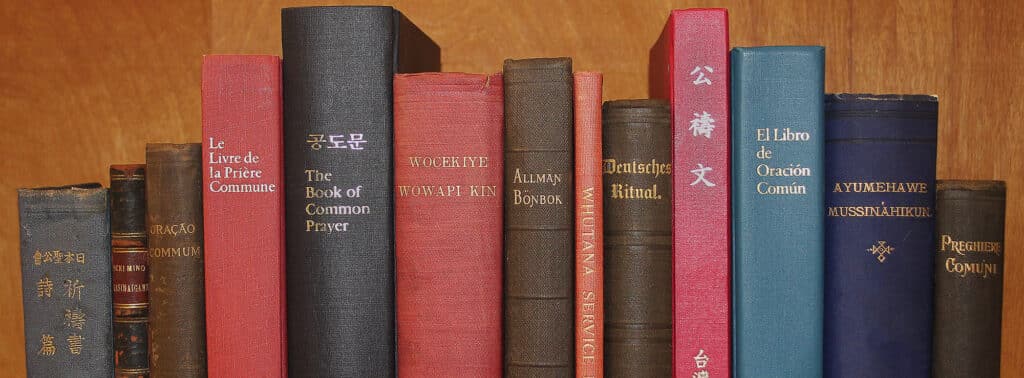

The Prayer Book was not just a unifying statement of practice and faith for the English-speaking church. Through language translation, it included other cultures in the United States and around the world as well. Only twenty-seven years after the 1790 Prayer Book was authorized, language translation enters the Journals of General Convention when a report from the Diocese of New York in the 1817 General Convention Journal commends Eleazar Williams, an Onondaga missionary to the Oneida, for his translations of “services and sermons into the Mohawk language.” He is mentioned again for his translation work in the 1820 Journal. At the same time, Rev. Henri L. P. F. Peneveyre began work on a French translation for the Church du St. Esprit in New York.

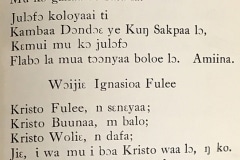

As the United States welcomed immigrants from the east and expanded to the west, the Protestant Episcopal Church increased its exploration of language translation as part of its missionary drive. French (1817), German (1835), Danish (1847), Spanish (1853), Portuguese (1859), and Italian (1880) translations were all resolved by General Convention over the century. Even if no committee was appointed to oversee a translation, missionaries either bought or wrote them. In 1829, missionaries to Greece sought funds to “purchase suitable translations of the Prayer Book and Homilies” for distribution. Bishop Boone, reporting from China to General Convention in 1847, simply began translating the liturgy himself. Further translation efforts were detailed in reports and letters to The Spirit of Missions, such as a paper written by the missionary Rev. Cook calling for a Prayer Book in the Dakota language.

Today, Prayer Book revisions and language translations continue with the goal that the texts reflect and “be enriched by our church’s cultural, geographical, and linguistic contexts,” to borrow from Resolution 2024-A224, and to form in the church a more perfect union.

- Hatchett, Marion J. The Making of the First American Book of Common Prayer. New York: The Seabury Press, 1982. p. 37-38. ↩︎