Legacy of Racism

During Allin’s tenure as Presiding Bishop he reestablished the “Black Desk” as the Episcopal Commission for Black Ministries, giving black clergy jobs at the national level that his predecessor Hines had overlooked.

“Let it be understood in my most Southern accent that I consider the mission of the Church to include the dignity of people and empowering those who are depressed, oppressed and deprived.” 37

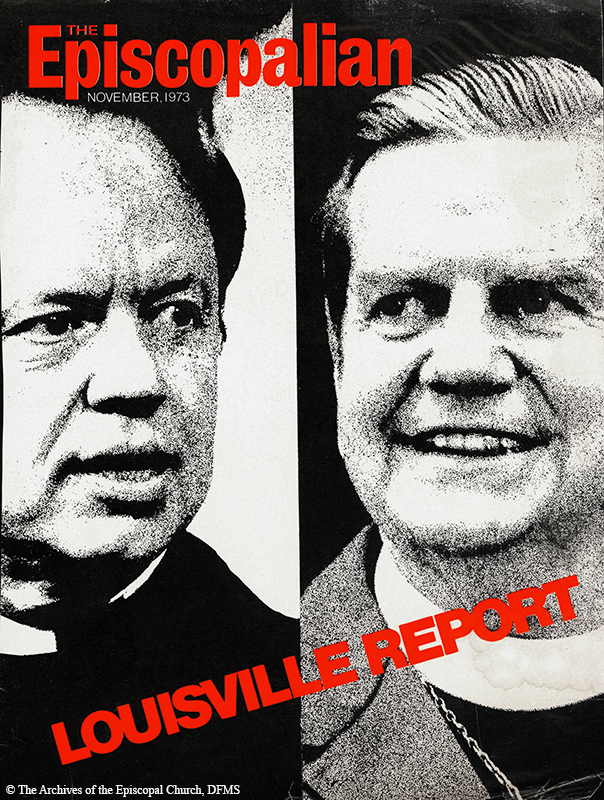

Doubts About a Southern Bishop

Allin was subject to intense scrutiny on his views and record in matters of racial injustice when his name was put forward as a candidate for presiding bishop. Because of a history and practice of persistent racism and segregation in Mississippi, many objected to Allin’s nomination, presupposing that he was too steeped in Southern racism and not interested in the problems of black clergy and Church members. Ann Allin said that when she heard “rumbles that this Southern Bishop” didn't understand the problem of race, she “wanted to shout from the rooftops” that they had “first-hand experience.”38 Contrary to how he was perceived by some in the Church, Allin was considered liberal in Mississippi when it came to matters of race. One supporter of Allin wrote in The Living Church, “to pin the racist label on him... is about as reasonable as to assume that the Bishop of Milwaukee must be president of a brewing company.”39

Hines and GCSP

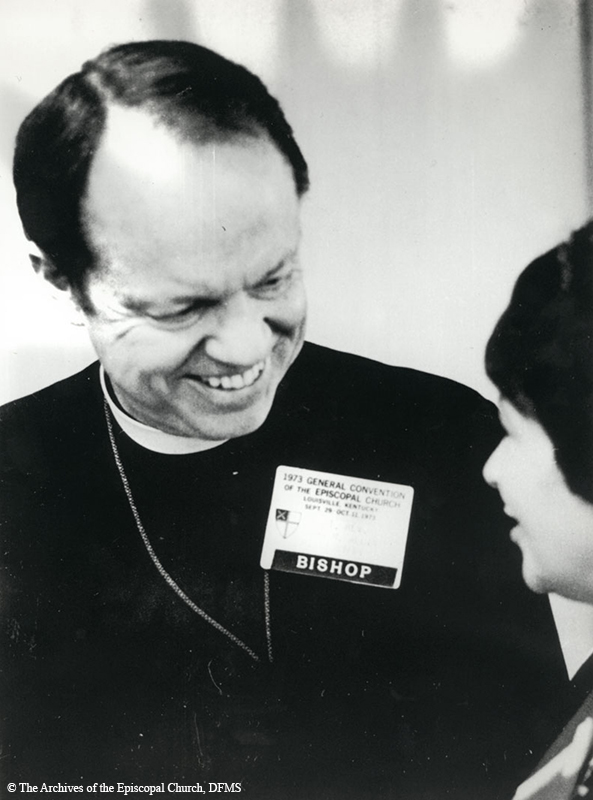

At the 1973 General Convention, it was not only Allin’s Mississippi background that gave pause to some about the future of race relations in the Church. If elected to the office of Presiding Bishop, Allin would also inherit the racial discord that erupted under his predecessor, John Hines. Many black clergy and lay persons were disillusioned by the way in which John Hines had carried out the General Convention Special Program (GCSP) adopted by the 1967 General Convention. The program was intended to address social problems such as racism in a broad way and on a national level, but to many it neglected the immediate needs of blacks within the Church.

Between 1967 and 1973, under liberal Bishop Hines, no black officer served on the Executive Council or national Church staff to develop and strengthen the ministry of African-American Episcopal parishes and missions. John Hines had removed the African-American priest, Dr. Tollie L. Caution, who had spent twenty-three years on the national staff of the Episcopal Church until Hines chose to re-constitute the new “Executive Council” staff. Some African-American clergy felt slighted when leadership of the GCSP went to a black layman, Leon Modeste, who had tenuous links to the Episcopal Church. Hines bypassed black clergy in appointing other key staff positions – a blow to those who had labored for years to end racial injustice and had experienced it first hand, unlike white liberals who had none, but spoke unabashedly on their behalf. African-Americans in the Church resented this slight and recognized the loss of power and voice on their issues as an institutionalized practice of racism.

Reestablishment of the "Black Desk"

Confirmation of Allin’s election as Presiding Bishop by the House of Deputies took an unprecedented amount of time. After his election, Allin met with the Union of Black Episcopalians and the black caucus of the Church and expressed his support for meeting their urgent requests. The GCSP was terminated by the General Convention, and under Allin, the “Black Desk” was reestablished as the Episcopal Commission for Black Ministries to “serve the needs of black churchmen” and in the words of the Rev. Franklin Turner and Bishop Harold L. Wright of ECBM, to “address the erosion of black clergy.”40 When he addressed General Convention, Allin finally took his opportunity “to shout from the rooftops,” as Ann said, and clear up any misconception about him, stating, “Let it be understood in my most Southern accent that I consider the mission of the Church to include the dignity of people and empowering those who are depressed, oppressed and deprived.”41