Election

“I think the election, my election as Presiding Bishop in 1973, reflected that the church was in a mood of compromise and they said we’ll choose this individual whose position has been pretty well established as in the middle of the House and on neither extremes. I was not the only one, but I was among those bishops who they really never were sure which way you would vote. There were some bishops in the House that, when the issue was introduced, you could almost guess what the core vote would be on either side of the issue. And then, it would depend on how the middle swung – and I was in that middle.” 22

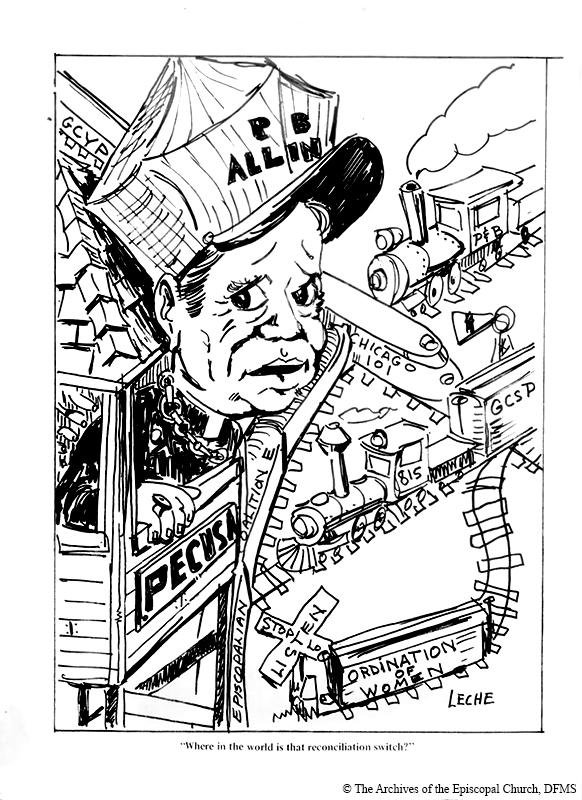

“...we pray he can get it all together without giving it all away.”24 Allin, as depicted in a 1973 post-election caricature in The Episcopalian. Allin had his work cut out for him following in the footsteps of his predecessor, John Hines. The caricature caption reads, “Where in the world is that reconciliation switch?” Depicted as a conductor, Allin’s enthusiasm for model trains was well known.

The Middle

Allin was recognized as a Southern conservative, but he did not intentionally ally himself with a single block of conservatives. He believed his election owed in part to his voting record, which did not betray a bias towards particular factions in the House of Bishops. Bishops never knew how he was going to vote. Some viewed him as a moderate—someone who could secure compromises. His election owed to his non-ideological practicality, which made him popular in the fraternal familiarity of the House of Bishops. Among many new Deputies, however, he was suspect. Their fear was that Allin would use compromise to lead the Church into backsliding on reform.

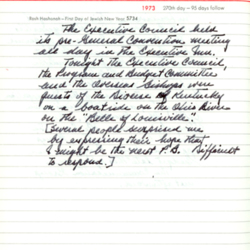

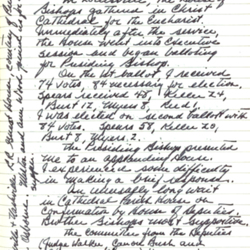

Allin was elected on October 4,1973, during the 64th General Convention in Louisville, Kentucky. He was one of five final candidates—three nominated by committee, and two from the floor—and won on the second ballot by the exact amount of votes necessary to elect. The House of Deputies took an unprecedented amount of time to confirm his election because some were unsure about what it would mean for the Church to have a Southerner in that office. Once confirmed, Allin asked for time to consider whether he would accept the position, saying, “I need to have twenty-four hours because I need to talk to the Lord, and I need to talk to Ann Allin. And if either of them indicate that they’re not going into this venture with me, I don’t intend to try it myself.”23 Prayerful reflection and Ann’s endorsement allowed Allin to accept the position and make plans for his twelve-year term as Presiding Bishop.