Racial Tension

“We are all alike because we are all different. Black eyes can share faith with blue eyes. Red skin and yellow skin and black skin and white skin can worship God and serve God together. The most practical opportunity to serve God is in serving and sharing with one another.” 15

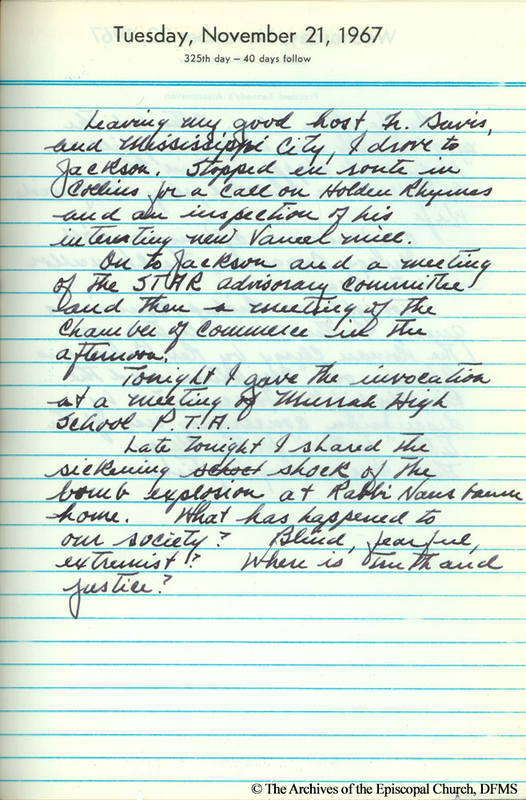

“What has happened to our society? Blind, fearful, extremist? Where is truth and justice?” Allin’s journal entry conveys his dismay after having learned about the bombing of the home of his fellow clergyman, Rabbi Perry Nussbaum, an anti-segregationist activist in Jackson. The Ku Klux Klan bombed Nussbaum’s Congregation Beth Israel in September and then his home in November 1967.

A Remarkable Challenge

Bishop Allin took on the great challenge of addressing the problem of racial turmoil within the confines and institutions of a conservative state seen as led by uncompromising local elites and public officials. Unlike some other Mississippi church and government leaders, Allin took a stand on the necessity for working out a solution to the race problem. His approach was for steady reform albeit gradual in application. He believed that the issue of racial injustice could be managed by local discussion and incremental negotiated settlements. What seemed like a pragmatic, problem-solving approach to Bishop Allin and other white leaders was considered part of a tradition of obstructionist delaying tactics to those seeking an immediate end to century-long indignity and oppression.

Bishop Allin sat squarely on the edge of a remarkable challenge to social bonds and cultural self-images. The Church was itself beginning to experience a wide divide among its own members that began with its decades-long anemic response to racial injustice. The flood gates of dissent opened to release institutional forces seeking justice, equality and a voice for marginalized members of the Church.

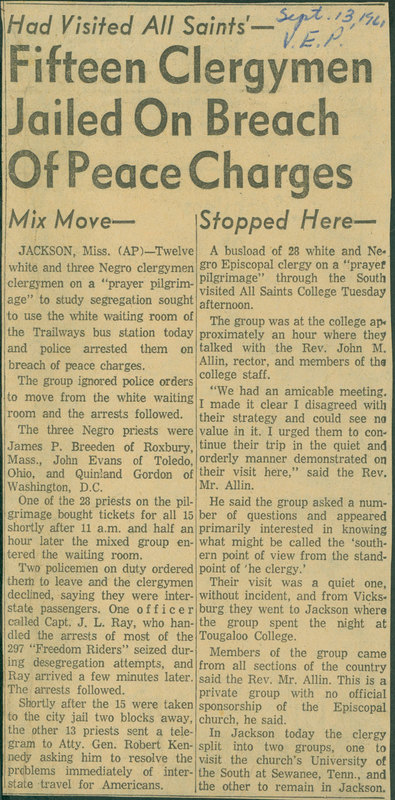

“Quiet and orderly.” 1961 Vicksburg Evening Post clipping details clergy arrests and Allin's response to a clergy group visiting All Saints’ College for the purpose of studying segregation.

A Desperate Situation

Faced with the daunting nature of racial unrest in Mississippi, Allin was determined to make a positive impact. Dean David Collins, his lifelong friend, told a story relayed by Allin about a visit he made to speak with John F. Kennedy. Allin asked the president if anything could be done about the racial unrest in Mississippi to which Kennedy replied that the power of the presidency is severely limited. Collins said that Allin confessed, “There I sat, looking at the president in his rocking chair, realizing he was unquestionably the most powerful human being on earth. He could in fact destroy the entire earth twice over. And yet, here he was, saying he just couldn’t do much in Mississippi.”16 Kennedy’s response aptly illustrated what Allin was up against in battling a perception of hopelessness that many whites had about change in the Southern state.

Allin’s faith did not allow him to see anything but possibilities in a desperate situation that left many of his peers feeling helpless. He set out to tackle the problem by shaping cooperation through conversation. He believed that solutions emerged naturally from the local experience of people living and working together.