Episcopal Passage: The First African American Bishops

The first two Black bishops consecrated for the United States, the Right Reverend Henry B. Delany (seated left) and the Right Reverend Edward Thomas Demby (seated right), following Delany's consecration at St. Augustine's College, Raleigh, November 21, 1918. Photo courtesy of St. Augustine's College, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Set within an American religious experience of lay and clerical rights in Church governance, bishops of the Episcopal Church have nevertheless been granted significant authority, prestige, and influence within the Church and society. After the mid-1800s, Black clergy members began to seek out the Episcopacy in order to achieve status, equality, and a platform for undermining opposition to the full participation of Black Episcopalians in the Church’s life.

It was not until 1863 that the first Black parish (the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas) was officially admitted into the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania, despite its commitment to follow the doctrine of the Episcopal Church since 1794. Reconstruction saw early efforts at greater participation in other ways. The consecration of first two Black bishops of the Episcopal Church, James Theodore Holly in 1874 (Bishop of Haiti) and Samuel David Ferguson in 1885 (Bishop of Liberia) set precedent for change and freedom albeit in underdeveloped overseas areas where competition from white episcopate candidates did not exist. Assignments to the domestic episcopate, however, would not occur until the next century.

The years following emancipation witnessed the exodus of Black church members from the Episcopal Church to other denominations more supportive of Black leadership and church membership. Common sentiment amongst the white Episcopal Church membership was one of resistance and neglect to the development of Black churches in the South. While Black Episcopalians were focused on the development of Black clerical leadership and the acquisition of voice and vote in the General Convention, the southern bishops proposed to General Convention in 1883 the establishment of separate and subordinate black missionary churches under the direction of the diocesan bishops. The Black Episcopal leadership responded to the ecclesiastical segregation and disenfranchisement implied by this legislation with the creation of the Conference of Church Workers Among Colored People (CCWACP), which was largely responsible for the legislation’s failure at the 1883 Convention.

A proposition to establish missionary districts along racial lines was proposed in 1904 as an alternative strategy to the southern segregation effort. The CCWACP supported this plan to offer Black Episcopalians a link to the national Church by allowing representation in the General Convention and supervision by Black bishops. Despite the repeated opposition received by the plan from Convention, the Conference campaigned for this option until its final demise in 1940.

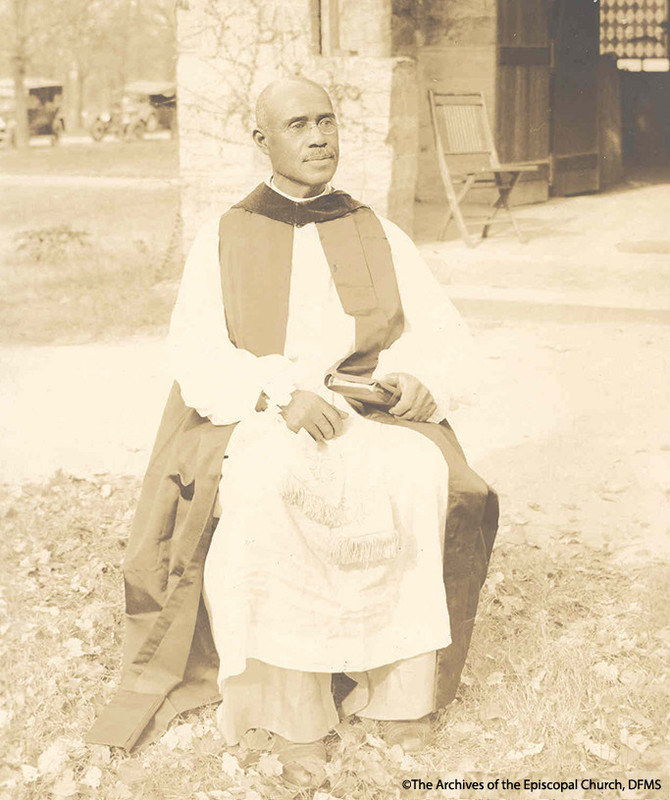

The Right Reverend Edward Thomas Demby (seated in center) at the end of a preaching mission followed by the confirmation of 4 girls, 3 boys, and 4 adults in Forrest City, Arkansas, c. 1930.

The Conference’s sustained push for greater participation led the 1907 General Convention to establish the so-called suffragan bishop plan in which the suffragan worked as an assistant to the diocesan bishop with no vote in the House of Bishops and no right to succeed to a position of full status as diocesan bishop. Despite ratification of the legislation three years later, the first Black suffragan in the United States was not elected until 1917 by the Diocese of Arkansas. The Right Rev. Edward Thomas Demby began his work in 1918 amidst controversy and challenges as Bishop Suffragan for Colored Work in the Diocese of Arkansas and the Province of the Southwest. In the same year, Henry Beard Delany was consecrated as a Bishop Suffragan in the Diocese of North Carolina and entrusted with the supervision of all the Black churches in the Carolinas. In spite of this designation, this achievement was not celebrated by many Black Church members who considered it a symbolic gesture made by a Church that in reality was still committed to segregation. The Episcopal Church denied the Black suffragans the real authority necessary to shape and guide the Church’s Black communities.

The sentiment of “separate but equal” prevailed within the Church as it did throughout the nation, despite the consecrations of Demby and Delany. Other bishops were consecrated under the suffragan bishop plan; the majority of the candidates were white except for three Black Episcopalians consecrated as bishops for service in Liberia. It was not until the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s that the next generation of domestic Black bishops took office in the American Church.