Leadership Gallery

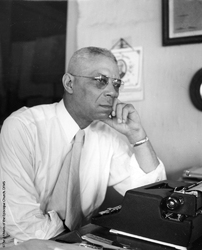

The Right Reverend Bravid Washington Harris, 1896-1965

The law of life is: ‘In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread,’ and we either eat it in the sweat of our own or somebody else’s and the latter doesn’t help much. Men develop as they work and labor for their own ends and manhood cannot be developed in any other way. Then too, we appreciate the things that are the result of our own labor more than those things that are presented to us by somebody else.

- Bravid Washington Harris

Bishop Harris was a tireless worker in the building of better interracial relationships. He achieved his purpose with honor and distinction over the course of forty years. At the time of his consecration as the eighth Missionary Bishop of Liberia, Harris was the only Black bishop in the active service of the Episcopal Church who went on to lead an effective missionary program in Liberia.

Harris was born in Warrenton, North Carolina on January 6, 1896. He received his education from St. Augustine College in Raleigh, North Carolina and Bishop Payne Divinity School in Petersburg, Virginia, both of which were affiliated with the American Church Institute. Following his graduation from St. Augustine’s, where he was commanding officer of the Student Military Corps, he entered the Officers’ Training Camp at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. He was commissioned First Lieutenant upon completion of the course and deployed to France to serve from 1917 to 1919 during the First World War. As first lieutenant, he was recognized for honorable service by the United States Government. Harris married Flossie Mae Adams on May 28, 1918.

After his discharge from the Army, Harris enrolled at Bishop Payne Divinity School to prepare himself for the ministry. He graduated in 1922 with a Bachelor of Divinity and an admirable academic record. Harris also held an honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity from the Virginia Theological Seminary, which he received in 1946.

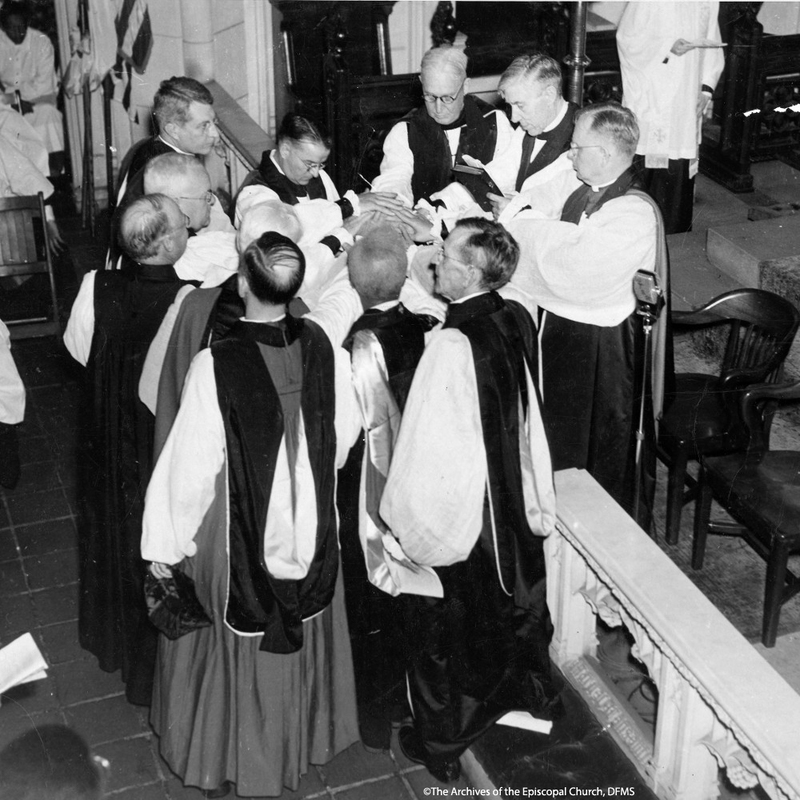

Consecration of Bravid W. Harris as the eighth Missionary Bishop of Liberia, April 17, 1945 in Norfolk, Virginia.

Harris was ordained to the diaconate in 1921 and to the priesthood by Bishop Delany the following year. That same year, he began his ministry serving the Warrenton, South Carolina parish of All Saints Church as Priest-in-Charge. In 1924 he left All Saints to begin his long rectorate at Grace Church in Norfolk, Virginia. For twenty years, Harris lead the Grace Church community which would grow to become the largest historically Black Episcopal parish in Virginia. Under the dynamic guidance of their rector, the parishioners of Grace Church evolved into a congregation that became recognized for their contributions to the community.

Harris filled the position of Archdeacon for Negro Work in the Diocese of Southern Virginia from 1937 to 1944. During this period, Harris also devoted his time to the Bishop Payne Divinity School as a trustee; the Norfolk Community Hospital as president; and the Norfolk Community Fund as director from 1934 to 1944. Harris resigned from Grace Church in 1944 to take a position with the National Council in New York as the first Executive Secretary of Negro Work of the National Council Home Department, a position he held for a year until his election and consecration to the episcopate.

Harris’ close association with the African American church earned him the qualifications and reputation that elevated him to the episcopate as Missionary Bishop of Liberia on April 17, 1945 in Norfolk, Virginia. He was the first Black American to lead the Liberian mission, which nonetheless retained a colonial relationship to The Episcopal Church. His consecration was a celebration of interracial fellowship with more than 1,500 people in attendance, a testament to the trust and wide admiration people had in Harris. As Bishop of Liberia, Harris was assigned the Church’s mission of “westernization and democratization” in one of the oldest missionary districts of the Church, one inherently complex yet teeming with opportunity.

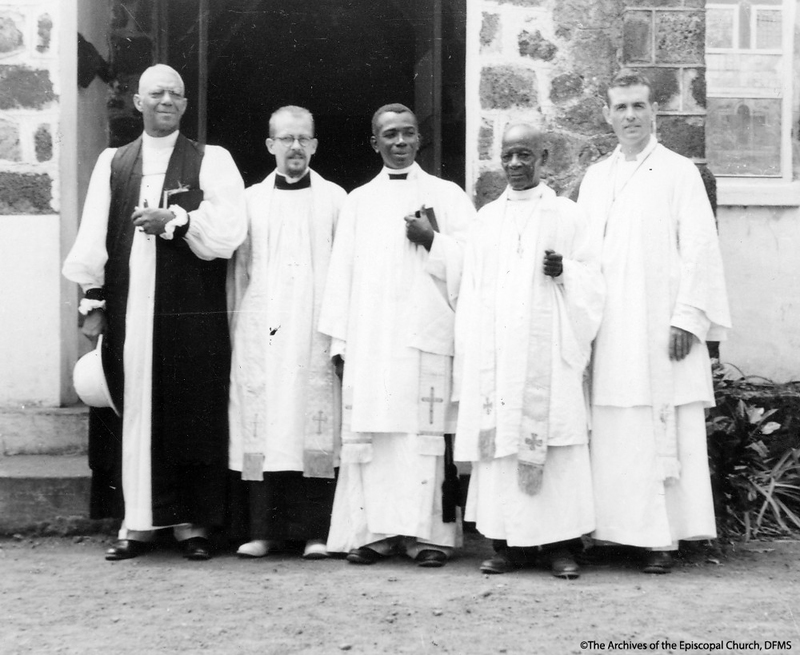

Clergy of Liberia, 1950. From left to right: The Right Rev. Washington Harris, Mr. Miller, The Rev. J.D.K. Baker of Monrovia, The Rev. J. G. Coleman (retired clergy from Robertsport), and The Rev. Edgar Robertson.

Liberia was two years shy of its bicentennial celebration as an independent nation when Bravid Harris succeeded Leopold Kroll as Missionary Bishop of Liberia. The patterns of tension and misunderstanding present among the different peoples of Liberia were familiar to him, reflecting the division of races and classes present in the United States at the time. The almost three decades preceding Harris’ episcopate were marked by events which impeded the Church’s progress in Liberia - a labor scandal in Liberia, two world wars, and the 1930s economic depression. Success in Liberia was further complicated by the lack of strong clerical leadership in the country. It was a period in the mission’s history that tested the endurance and patience of the Church’s faithful. The devotion and integrity consistent with Harris’ decision making and leadership would help him to overcome the ever-present obstacles and to assist Liberians in reaching their potential.

Liberia would ultimately benefit from Harris’ experiences as rector and archdeacon in urban and rural work and from his fearless commitment to human rights. Harris first concentrated his efforts on building schools and churches in support of improvements to the educational system. After twenty years of closure, he rebuilt and reopened Cuttington College to serve as the center of the Liberian mission. Classes in Christian theology, agriculture, health, and education were offered to men and women for the development of skills that would ultimately benefit the work of the Church and the whole of Liberia. Harris believed the women of the Church were an underutilized resource and advocated both theological and traditional education for them.

The theological school at Cuttington was a primary focus for Harris. Since the days of Bishop Payne, the Church had desired a staff and facility within the republic that could train Liberian ministers and laity. This could not be accomplished, however, until the Liberian lower schools were strengthened. Steady improvement was made in this area including the construction of five new schools. Bishop Ferguson Memorial High School was a noted success. At the time of his death in 1965, the majority of active Episcopal priests in Liberia were trained at Cuttington and ordained by Bishop Harris.

The severe climate and lack of scientific and technical expertise in Liberia gravely impacted the quality of life for native Liberians as well as the direction of Harris’ mission. In spite of Liberia’s harsh terrain, Harris traveled the country extensively, witnessing first-hand the hardships faced by the people of Liberia and the limited availability of medical services. The impact of these trips resulted in the establishment of tropical disease research and public health laboratories, some in areas that had never before been home to a resident physician.

Bishop Harris’ philosophy of evangelism was simple. For purposes of a sustainable Church, he believed Christianity should be planted and nurtured locally by the inhabitants of the area rather than by a foreign church. Harris’ evangelism centered on the completion and improvements to existing church buildings; improvements to clergy salaries, quality of work, and pastoral care; involvement of qualified local leadership in policy making; and the thorough training of future clergy and church workers. His progress included the founding of four self-supporting churches: Trinity Church; St. Thomas, Monrovia; St. Paul’s, Greenville; and St. Mark’s, Monrovia. Although not completed during his tenure, Harris began efforts towards the construction of Trinity Cathedral in Monrovia.

By the end of his jurisdiction, Bishop Harris’ work as an outstanding and sensitive administrator and an imaginative leader, won for him the profuse admiration of the people of Liberia and his American Church colleagues. President Tubman expressed the sincere gratitude of the nation at Harris’ retirement in January 1964 saying, “The Protestant Episcopal Church in Liberia has been fortunate to have had the benefit of Bishop Harris’ vision, depth and breadth of understanding, humility of spirit, human compassion, deep interest in evangelism and yen for hard work...In addition to his building programme, the Bishop has promoted the idea of a self-supporting church as the sacred obligation of a free people in a land where religion and the founding of the nation were coeval...The personal relationship that has existed between Bishop Harris and myself has been intimate and mutually beneficial...During the nineteen years of our association I have had every occasion for increased confidence, respect and affection for the Bishop...Another reason for my tender feelings that must be brought to mind at this time...is the fact that we are of the same age, or what we could call in our Liberian colloquialism, ‘crowd of boys’.”

After serving nineteen years in Liberia, Bishop Harris retired and returned to the United States. He worked briefly as the president of the Association of Episcopal Colleges before his death in an automobile accident at the age of 69. Harris also authored A Study of Our Work. [Sources]