Leadership Gallery

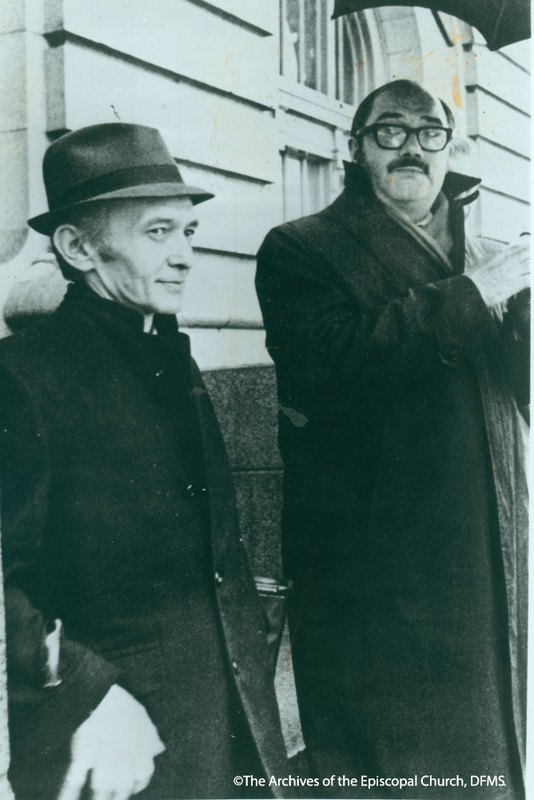

William Stringfellow, 1928-1985

The central witness of the Church in the racial crisis is to bear the rejection of white people by Negroes, provoked by three centuries of exclusion and exploitation of Negroes by whites, and to bear this terrible, compounding hostility between the races without protest or complaint, without concern for innocence or guilt (that is for God’s judgment and forgiveness to reveal), in other words, in the love of Christ for the whole world.

- William Stringfellow, My People Is the Enemy, 1964

William Stringfellow was a lay theologian and attorney whose long career in social activism began in his junior year at Bates College, when he organized a sit-in at a restaurant which was refusing service to African Americans. Stringfellow’s theology and his dedication to equality and social justice were inextricably intertwined, and while as a lawyer he devoted himself to representing and defending the vulnerable according to civil laws, his remarkable response to injustice in society was rooted in his Christian convictions.

Stringfellow was born to a working class family in Rhode Island in 1928, and grew up in Massachusetts. He attended Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, and received a scholarship to study at the London School of Economics. After serving in the U.S. 2nd Armored Division, he finished his education at Harvard Law School. Upon graduation in 1956, he moved to a small apartment in Harlem, and began a practice representing his neighbors, largely low-income African Americans and Hispanics, in their legal fights against commonplace injustices caused by rapacious landlords, unequal access to social services, and the tendency of the judicial system to ignore and devalue the impoverished. During this time, he became a founding member of ESCRU.

In Harlem, Stringfellow witnessed first hand the ravages of poverty on the human soul, which he documented in his 1964 "autobiographical polemic," My People is the Enemy. The work would later draw criticism from the Rev. Moran Weston, rector of St. Philip’s Church in Harlem, for what Weston saw as its oversimplified portrayal of the Black experience as universally soul-crushing. That reality underappreciated the numerous Black men and women who had nonetheless constructed comfortable and fulfilling lives for themselves. Stringfellow advocated for addressing racism in its insidious forms. He argued that the impact of the “platitudes of tolerance” in Northern cities, compared with the reality of the indifference, hostility, and condescension with which African Americans were actually treated there, was psychologically more damaging to those who endured it than was the open segregation of the South. He concluded that “the decisive front in the racial crisis in America is the urban North, and not the South.”

Socially and politically, Stringfellow often found himself aligned with the “liberal” sectors both of the Church and of society. In addition to his regular legal practice, he defended the arrested members of the ESCRU “Prayer Pilgrimage” and the first women to be irregularly ordained to the priesthood; he harbored Catholic anti-war activist Daniel Berrigan (wanted by the FBI for burning draft cards); he defended Bishop James Pike against heresy charges; and he was a vocal critic of homophobia. However, he was not a partisan of internal Church politics. He was adamant that the Church’s role was constantly to defy the status quo, whatever that might be at a given time. Theologically he often differed with social liberals, and insisted unwaveringly that the Bible, approached honestly and not viewed through the distorting lens of even the most noble social theories, should be the sole arbiter of a Christian conscience.

Though Stringfellow himself was sometimes guilty of the subconscious racism that he famously pointed out was present even in “nice, Northern liberals”– for example, in his pronouncements upon the authenticity or qualifications of leaders of the Black community, and his free use of terms like “Uncle Tom” in his discussions of race – his witness for racial justice was sincere, fervent and striking. His work was a manifestation of his deep belief in the power of God’s love to liberate mankind from the selfishness and fear that divides us: “In that freedom is the love and unity among men which can endure death for the sake of all, even unto a man’s own enemy, even unto my own enemy, even unto myself.”

Stringfellow's companion of fifteen years, the poet Anthony Towne, with whom he shared a house and a dog, passed away in 1980. A Simplicity of Faith, a meditation on the grief he felt following Towne's death, was published in 1982. William Stringfellow died in 1985. [Sources]